Tales from the Biographer’s Desk

Regular Unzipped readers may remember that I retired from Levi Strauss & Co. in June of this year, after 24 years as company Historian.

Retirement does not mean slowing down, though. My labor of love for the next year is writing the biography of the founder, Levi Strauss himself. I spent my career tracking him down in the historical record, because all of the records about him and the company went up in flames after the earthquake of April 18, 1906. He was pretty elusive, but I finally found enough material to get a sense of who Levi was, how he lived, and how he contributed to American business, philanthropy, and, of course, clothing.

The book won’t come out for a couple of years, but I am finding so many great stories, that I didn’t want to wait to share some of them. So with this post, I am inaugurating an occasional series about my adventures called “Living With Levi.”

Let’s start in the year 1894.

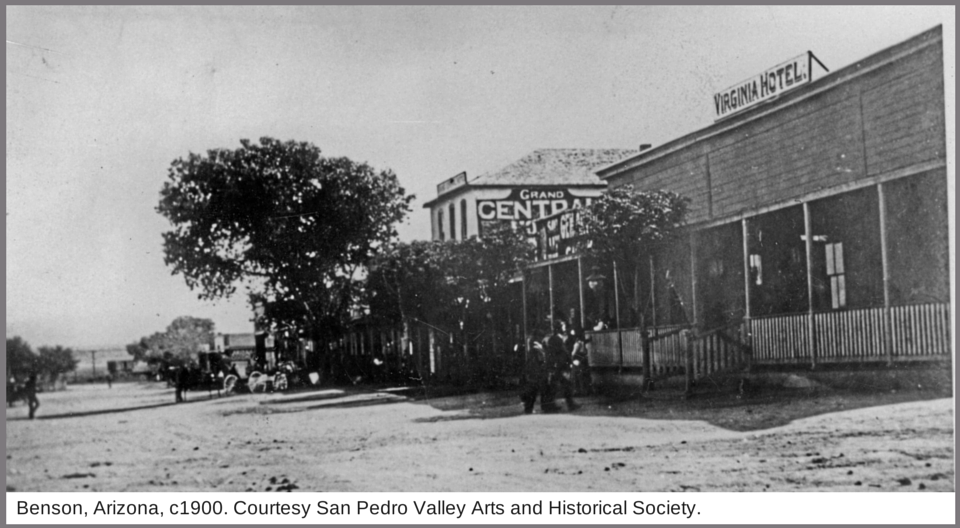

Early in the week of December 10 of that year, two men stepped off a Southern Pacific train in Benson, Arizona and walked through a drizzling rain across Main Street toward the Grand Central Hotel. There, they wrote their names in the hotel’s register: Adolph Sutro, and Levi Strauss.

Left: Newly-elected San Francisco mayor Adolph Sutro, 1894 (Courtesy Dr. Robert Chandler). Right: Levi Strauss.

Benson was an important hub for the Southern Pacific railroad, and millions of dollars of mining wealth from nearby Tombstone passed along its rails. You could get to Benson from San Francisco on the train in just a little over two days. Men from all walks of business found themselves in town, and the names Sutro and Strauss were certainly familiar throughout the West.

Sutro, for example, had made millions with the “Sutro Tunnel,” which drained off the excess water in the silver mines of Nevada’s famed Comstock Lode, making the ore easier to extract. He held property all over San Francisco, opened a public bath for his fellow residents, and had just been elected mayor of the city.

Strauss was a prominent San Francisco merchant and the man behind a new kind of denim work pants, reinforced with metal rivets for strength. Ads for his famous trousers appeared regularly in the Tombstone Epitaph newspaper, which published the list of the Grand Central’s arrivals in its December 16 issue.

The appearance of these names on page three of the Epitaph, next to the story about a stage robbery, most likely didn’t cause a stir. It should have, though.

Because the men were impostors.

Both Sutro and Strauss were in San Francisco when their doppelgangers got off the train. Levi Strauss was in court telling Judge Hebbard why he was unable to serve on the Grand Jury. Adolph Sutro was talking with his staff about the upcoming visit of General Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, who would arrive in San Francisco on the 17th.

In the days before mandatory identification and wide use of photography, it was fairly easy to pretend to be a prominent figure from another state, as long as you wore a broadcloth suit and, considering the threatening snow that December in Benson, a fine but heavy overcoat.

No one will ever know who they really were, but the two fraudsters doubtless received excellent service during their stay at the Grand Central.